MICHAEL DORET’S WORK SEEMS familiar. Bold and colorful lettering with complementary graphics evoke memories of roadhouse signs on Route 66 or the bright marquees of the Great White Way.

Growing up in New York City, Doret was surrounded by classic mid-century American icons. He lived in Brooklyn, near Coney Island, where he came face-to-face with bold and freaky graphics and signs. Those influences shaped him and his work, as Doret reveals in this interview, conducted at his Los Angeles studio.

You grew up near Coney Island. When did Coney Island transform from an amusement park to a source of inspiration?

I wasn’t really aware of how influential that place was until a couple of years ago when I rediscovered an old photo of my brother and me in Coney Island. I had just never thought about it. I looked at the photo in which we’re surrounded by all this colorful signage, and I had an epiphany that all this stuff had made an indelible impression on me and had heavily influenced me to a very large degree in terms of the work that I’d eventually become known for. See this guy? →

Around the same time that I found the photo, I just happened to find this placard—the Tilt-A-Whirl company from the photo was still in existence, and the placard was actually in that old photo I spoke of. My work has so much in common with all the banners, signage, placards and such that would surround you in Coney Island that I concluded that it was no accident that I ended up working in the genre that I do. So, to answer your question, it wasn’t until fairly recently that I knew that Coney Island was my Muse.

My dad had worked on Broadway in Times Square, and I also came to realize that “The Great White Way†had had the same effect on me as Coney Island. It had incredible billboards, signage and advertising. I remember an actual living logo—Mr. Peanut—walking around on Broadway. There were also the Brooklyn Dodgers and plenty of baseball ephemera, which I was surrounded by at that time. Now I know that all that stuff was somehow working on my brain and pushing me toward my predilection for bold graphics and letterforms. It’s as simple as that.

You graduated from Cooper Union in New York City. One of your first jobs took you to the studio of Ed Benguiat, who along with the International Typeface Corporation, ignited the type industry of the 1960s and 70s. What did you do in his studio?

He didn’t have his own studio. He worked at a company called Photo-Lettering, which was one of the first and certainly the largest photo-typesetting house in the world. Their font library literally filled volumes. House Industries bought a lot of these fonts and has digitized them. Anyway, I worked there as Ed Benguiat’s assistant for a year. He ran a little division in Photo-Lettering where they did more custom work for clients who just didn’t want straight type set. We would take the film output and he showed me how to customize it, whether it was drawing with ink on top of the film, scraping away the emulsion on certain letters and filling in other areas, cutting it apart and moving it, or all of the above. It was all very primitive compared to what we do now on the computer. My getting that job right out of school was a total fluke.

When I was at Cooper, I had a typography class in which one of the assignments was to design a font. Mine came out pretty well—for a student—and it was suggested that I submit it to Photo-Lettering. I did, and they “bought” it and it’s in their Alphabet Thesaurus Vol. 3. It’s something I did as a student and now it’s a little embarrassing, but kind of funny. At the time I didn’t even give it a name. So they named it “Doret Shaded” because it had a dimension to it. As a student I was such a contrarian. I thought “I’m just going to reverse the weights to be where they wouldn’t ordinarily be” so that the verticals were thin and the horizontals were thick.

So you freelanced while you were working at Photo-Lettering?

No, I did that afterwards. I was an art director for a sales promotion agency, and I held several other staff positions over the next few years, until I went out on my own. I was getting freelance work and taking it home at night. For some reason, the work that I did always seemed to come back to my drawing letters. So I started getting more and more work until it got to the point that in order to continue, I’d have to quit my day job.

Did you have a mentor or collaborators when you went on your own?

While I still had my day job, I was taking my portfolio around and somebody suggested “Why don’t you go up and see this illustrator named Charles White III?” Charlie was a pretty big name in the illustration field at the time, being one of the leading airbrush artists of the day. He’s currently being lauded in a book called Overspray—about him and the three other leading airbrush artists of the time. So I went to see him.

He was actually the one that convinced me to quit my day job and go out on my own. He offered me a drawing table in his studio. I took his suggestion, quit my job and started working out of his studio. In addition to the work I brought in for myself, he started hiring me to help him with his illustrations. One piece we worked on was the “Octopus” record jacket. I designed the lettering that went around the bottle. To complicate matters I had to figure out how it would go around a curved surface in perspective. We had no computers to help us in those days.

You bent the lettering around the lid too?

Yes.

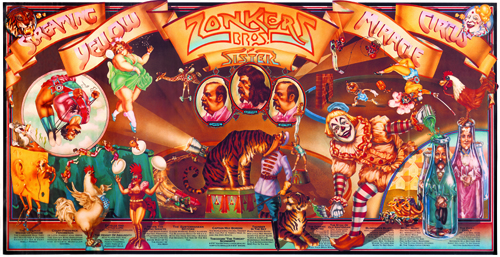

So I started doing my own work and doing stuff for Charley on his illustrations. I helped him design a huge poster for a popcorn/candy called “Screaming Yellow Zonkers”. At that time, I would draw the lettering on tracing paper, then rub it down on his illustration board and sometimes ink it in. Or he would paint it. He was looking for ideas on how we could design and integrate all the typography into the illustration, and I came up with the banner idea. He loved how I could make the ‘Z’ and the ‘S’ reflect each other.

So what it really became about was this: We ended up doing this thing with illustration that no one had done in a long time—which was to combine the typography and the image into one and make them completely interdependent—not just leaving a blank space into which someone could insert type. Just one integrated, cohesive image. And we did a lot of that stuff. I don’t know if it’d ever really been done that way before or since. Like that Octopus cover, the title and all the information was all there, integrated into the image. There was nothing else required.

You came up professionally in the 1970s. It was seemingly the golden age of design and advertising. You were disappointed with how type was used with image, why?

To my way of thinking, the art of hand lettering was at a low point. We’d gone through the ’40s and ’50s and into the ’60s with tons of lettering being done by hand. I think that discipline was being lost because of photo typesetting—the same way that certain disciplines are being lost today because of the computer. There was hand lettering still being done—but it didn’t excite me. There were what I’d call the Lubalin/Carnase and the Rudolph deHarak schools of lettering and typography. They were more classically influenced. What I did and still do is influenced more by pop culture, and is more instinctive rather than learned. The work being done by the more classically trained and influenced designers like Lubalin and Carnase was not really that interesting to me. I was trying to fill a void in an area that at the time nobody else was filling. And I first got involved with it through working with illustrators like Charles White III and some others like Doug Johnson. Through them, I was being indoctrinated into the vintage/retro thing. At the time we were really at the beginning of that sensibility. In the early ’70s there was the beginning of a new appreciation and awareness of the aesthetics of the ’30s, the ’40s, Art Moderne, Art Deco and into the World War II period. Looking back to the past in that way was not something I’m sure had really been done up to that point. Of course it seemed like there had always been antique shops, but antiques were considered something from the turn of the century, something to be admired but perhaps not emulated. A friend of mine named Kenny Kneitel (the grandson of Max Fleischer—the creator of Betty Boop) had opened a vintage shop named Fandango, which was one of the first of its kind. He dealt with things like Bakelite radios and a lot of other memorabilia that were, before then, considered junk. All of a sudden they were now being looked at again in terms of their design qualities, and as things to be admired. So I got involved in that whole world. That kind of thinking got instilled into what I was doing and just moved me completely away from classically oriented design.

Then other people started picking up and emulating what I was doing. That kind of rubbed me the wrong way for a while. In perspective, those artists ended up going off in their own directions and putting their own personal stamp on their letterforms work. Over the years, I feel like I’ve brought people around to looking at lettering design a little bit differently. Now, what I do, may seem to some a little outdated. But I try not to repeat myself and try to always challenge myself in other ways. I don’t want to keep repeating the same work I’ve always done…to keep repeating my past successes.

The KISS album cover left an impression on me as a kid.

Apparently it left an impression on a lot of people.

You said you drew your inspiration (for the KISS cover) from a job for a (Japanese) magazine cover, IDEA. Where did you get your inspiration for that cover?

The magazine was doing a feature on my work and they asked me to come up with a cover for that issue. I did the cover image to look like a shooting gallery. So the inspiration probably goes all the way back to Coney Island—but the direct inspiration was also vintage tin toys and tin litho target games. Anyway I did the IDEA cover first and the whole KISS / Rock and Roll Over thing came afterward. I loved the way the IDEA cover came out, the way I had them print it in Pantone colors—it almost felt like a silkscreen. I really wanted to go that route again. As the members of KISS were wearing Kabuki-style makeup, the Japanese-y approach I did on the IDEA cover seemed a perfect match. So I came up with that graphic and used a similar color scheme and look. We even did it in five flat colors—not in 4 color process.

(The KISS cover) was like a shooting gallery then?

Not at all. It turned out to be more like a mandala, more Asian-influenced. I was just going for the look I had come up with on that other cover. The visual theme I chose came out of the album’s name, the “Rollover†thing. There was no “right side up” to that cover…An interesting side-note is that after all these years since I did that work for KISS, they’ve come back to me and asked me to design their next CD cover. It’s a big project, and at the moment, I’m totally immersed in it.

You created designs for magazine covers, posters, postage stamps, what am I missing?

I’ve done all kinds of stuff. Logos, record labels, t-shirts, you name it!

You describe yourself as a letterforms artist.

My whole career I’ve struggled with the dilemma of what to call myself. To say I’m a “lettering artist” doesn’t really describe what I do. “Font designer” only describes one discipline that I’ve gotten into recently. I do a lot of different things—but they all usually involve letterforms in one way or another. To use the term “letterforms artist” broadened the description a little bit and moved it slightly away from “lettering”. A “letterer” is the person who, for example, does the lettering on a book jacket over a photo or illustration. Although I’ve done that, it’s only a small, piece of the puzzle. I don’t know if “letterforms artist” is the answer, but it begins to address what I do. When it comes down to it, I’m just a guy who likes to do what he likes to do. I don’t want anyone to tell me what direction I should take with my work. I don’t like to follow trends. But I might be more successful if I did.

What sort of reference material do you keep?

I have a lot of books. If I was a real collector I’d collect things like tin toys. I have some character trademark stuff like “Aristocrat Tomato” the Heinz 57 tomato juice character, “Reddy Kilowatt” and “Mr. Peanut”. But instead of becoming an avid collector of this stuff, I just ended up purchasing books on these subjects I just don’t have the room to collect all the stuff I’d want. There are so many books out there by people who have amassed huge collections of all the stuff that interests me. You can also find plenty of reference online. I look for oddball stuff. I like the stuff done by untrained eyes—people who didn’t know the actual “rules†and didn’t know they were breaking them. There was this online collection of old record labels that just blew me away. There’s just so much available out there that was never accessible before to someone like me. I pull a lot of this stuff offline, creating my own archives because I’m afraid that one day it’ll disappear from the web.

Your design for “Bedlam Ballroom†by the Squirrel Nut Zippers received a nomination for best recording package during the 44th Annual Grammy Awards. It’s a fun piece and strangely hypnotic (for the animation). Your Muse took you one way and the client moved you in another direction.

Not a totally different direction. They knew they wanted this to be in the “roadside” genre, like a motel or a roadhouse neon sign. My initial thought was to make it a little more risque, because they wanted to give it a really outrageous feeling. I guess I may have seen some old signs where you have the neon that has a couple of positions that animate as they go on and off in sequence. So for this sign, I was creating for the cover I had the main lettering flanked by two women…in outline neon, no real detail of any sort…where first you see them with drapery…then disrobed revealing the women’s figures. The lone female member of the group didn’t want any imagery that she considered sexist. So we went back more towards Coney Island imagery again.

The Jewish Zodiac was a departure for you because this assignment required you to incorporate photos of food. Was it a labor of love?

Yes it was, and it was also a challenge. I started with photos supplied by the client. There were so many steps I went through that I can’t really tell you how I did it, but I can say that I used both Photoshop and Illustrator. I enjoyed the process of making the photos very graphic and posterized and applying my own color palettes to them. The idea was that these pieces would be silkscreened on T-shirts, and I had to come up with a way of making both the design and the photos one uniform palette.

How much of the lettering was done by hand and how much was typeset?

It was all hand-lettering with the exception of the smaller text copy and the lists of years. Technically the smaller text was also done by me because I used a font I created—Bank Gothic AS. It’s my version of Bank Gothic to which I’ve added a complete set of lowercase letters. That lowercase was something that, for some reason, Morris Fuller Benton never did.

What compelled you to create the lowercase of Bank Gothic?

Well, I love Bank Gothic and I had used it all the time. It’s a very popular typeface, but I asked myself why doesn’t it have a lowercase, and what would I do if I designed the lowercase? I had the thought that maybe I should do it—so I did it, and thought that people would eat it up. But it hasn’t turned out to be one of my most popular fonts. What I probably need to do is to expand it into different weights, and maybe into a wider version, more extended.

It’s not your first though?

No. My first digital font was Orion MD.

And that came from a trip to Paris?

Well, I picked up this baked-enamel sign “Gevaert Photo†at a Paris flea market. I remember looking at it and thinking that I really liked the way that those letters connected. I hadn’t seen a script font that looked anything like it. I loved the upright, geometric quality it had. So I did a font, called it Orion, and put it out there. I’m really happy with it, but it may not be what people are really looking for these days.

Did this font Orion become the new chapter in your career as a designer?

That’s when I decided that doing fonts might be a challenging and interesting chapter in my career.

That wasn’t too long ago.

2002, 2003. Font design is an area I had always thought about—ever since that font I did at Cooper Union which ended up at Photo Lettering—but had never followed through on. Actually when I was sharing a studio with Charles White III, I did a font for this movie project we worked on together. You know how in silent films you’ll see a panel come on full screen with text that will tell you the dialogue? Well, this was an early film from Merchant/Ivory Productions called “Savages”, and they wanted it to have those kind of title cards. It was a 1930s period film, very extreme Art Deco, so I designed this typeface which I called Chrysler to use on all the title cards, film credits, and even the title treatment for the film for the ads and posters. We had all the letters, numbers, and punctuation photographed so that we could actually set the type on what was then called a “typositor”—a photo-typesetting machine, and so we had all the words set. I don’t know whatever happened to that typositor film.

You did that all by hand?

Yes, you can see that what I’ve scanned is from what’s left of the art that’s survived. This was originally drawn with a Rapidograph in ink on vellum. Many of the curves weren’t compass curves, and I felt that using french curves was cheating. Ed Benguiat had showed me how to take a rapidograph and do beautiful, tight curves by hand in tiny, little stroked increments. I think I would have gotten Chrysler done a lot quicker if I had used french curves and other mechanical drawing aids. I was such a purist that I thought doing that would be cheating, and I might not exactly get the curve I wanted. Why should I settle for a curve that’s only 95% of what I wanted? Make it exactly. I’ve wizened up a bit since then, but I’m still kind of a purist.

How did you develop Orion?

When I did Orion—which was my first font after all those years—it was done for the computer, and after years of experience drawing letters. I’d done Chrysler in the ’70s but Orion, I consider to be my first real font. When I first released it I got a lot of comments to the effect that each word set in Orion was like creating a little logo. I don’t totally understand how what I do is different from what other font designers do. But here’s what I get from talking to people: the gist of it is that I come from this other place, that all my years of experience doing one–off lettering related pieces has informed my font design process in a way that separates it from most other font designers. So maybe I do it a little bit differently than somebody who’s coming from a background of purely designing fonts.

Some of the letters offered very big challenges because in a connecting script the every lowercase letter has to connect somehow with every other lowercase letter. At that point I wasn’t dealing with OpenType, so I wasn’t able to fall back on the fact that if two letters didn’t connect properly I could always do a special ligature or alternate. Also, I felt challenged to make each letter interesting. I wanted each letter to be a beautiful design in its own right. And that’s probably the wrong way to do it because you really have to think in terms of the whole picture. There are lots of ways traditional font designers think that I probably don’t, and need to get used to. I’m getting there now but I wasn’t thinking in those terms when I started making fonts.

Metroscript is getting rave reviews. What was it’s inspiration?

Well that design I completely made up out of my head. I had always put words with letterforms like that into my jobs. Basically it’s an amalgam of various ’40s and ’50s scripts. There was this one job I did for the Post Office that required me making a lot of words in that script style.  I painstakingly lettered all of it. There must have been 30 or 40 words—a huge job for me. So what happened was this: I was in contact with Stuart Sandler who runs two font houses—Font Diner and Font Bros. Stuart’s been my font creation guru. I was talking to him about what I should do next in terms of creating a new font. He said I should look at my work, that maybe there’s something I’d find in there that could be applicable to becoming an unusual font. So I put together a bunch of word samples from past projects including a few words from that Post Office job and sent it to him. He basically told me that if I could figure out how to make that script into a font, that it would be huge. So I started working on it. I thought it was going to be really difficult to make it work, to make every character to link up properly with every other character. But what really made it possible were the features of OpenType. When I created Orion I used Fontographer, the old workhorse of digital font creation. Since then, FontLab had come on the scene. With FontLab you can create fonts which literally have thousands of glyphs. You can have any amount of alternate characters. You can code it to set type in a way so that as characters are typed they change before your eyes, depending on which character precedes or follows another. Mark Simonson, a fellow lettering artist, did the open type programming for Metroscript, and did a brilliant job. I couldn’t have done Metroscript without him!

I painstakingly lettered all of it. There must have been 30 or 40 words—a huge job for me. So what happened was this: I was in contact with Stuart Sandler who runs two font houses—Font Diner and Font Bros. Stuart’s been my font creation guru. I was talking to him about what I should do next in terms of creating a new font. He said I should look at my work, that maybe there’s something I’d find in there that could be applicable to becoming an unusual font. So I put together a bunch of word samples from past projects including a few words from that Post Office job and sent it to him. He basically told me that if I could figure out how to make that script into a font, that it would be huge. So I started working on it. I thought it was going to be really difficult to make it work, to make every character to link up properly with every other character. But what really made it possible were the features of OpenType. When I created Orion I used Fontographer, the old workhorse of digital font creation. Since then, FontLab had come on the scene. With FontLab you can create fonts which literally have thousands of glyphs. You can have any amount of alternate characters. You can code it to set type in a way so that as characters are typed they change before your eyes, depending on which character precedes or follows another. Mark Simonson, a fellow lettering artist, did the open type programming for Metroscript, and did a brilliant job. I couldn’t have done Metroscript without him!

I’ll show you the glyph palette on this font I’m working on called Deliscript. (now finished). I’m doing tails again like I did in Metroscript, and there’s 120 of them in six different styles. They’re variable length so people can use it to fit a short word, medium word, long word, whatever. The amount of times you type the underscore key determines how long the tail is. OpenType has all kinds of features that can be taken advantage of. It’s great to be able to look into the glyph palette to see what’s in the typeface.

The influence of Deliscript?

I’m always looking for inspiration. The Gevaert Photo sign was a jumping off point for me for Orion. In similar fashion, I was looking at the lettering that made up the Canter’s Delicatessen sign and somehow saw something in it I could take off from. The lettering in the sign may not resemble what the font ended up looking like, but I saw some interesting facets to it that I thought I could appropriate. I liked the idea of an upright script with the two-story ‘e’, and how things were connecting in it, and I liked its proportions. Anyway it started percolating in my head. I named it Deliscript for fun, but the font really has nothing to do with delicatessens. It could really be for anything. I hope the name doesn’t limit people’s uses of it—that it doesn’t suggest to them that they should only use it for menus and restaurant logos!

Where did you start? Lowercase, uppercase? Did you start writing words?

I just started with the letters for the name Deliscript, and created a sample. The way I used to work was I’d make very detailed drawings, plot angles and so on, and make all kinds of notations so that everything would be precisely worked out. As years have gone by working on the computer, and as I’m getting more and more comfortable with it, I’m doing less and less tight, finished drawings and just doing more looser drawings, just to get the sense of what I’d like to do. Now I’m scanning those looser drawings and then doing in the computer what I’d used to do in the tight pencil stage—all the measuring and plotting of angles, working out consistent widths, etc. But it doesn’t eliminate for me the requirement of still having to draw. And I can’t just start drawing in the computer as some people do on a Wacom. My pencil drawings have gotten a lot looser and I can amplify the drawing much easier now in Illustrator. Anyway this is the only drawing I did. I ended up with these certain letterforms that were in the letters of the name. I just started taking the pieces of these letters and started pulling them apart and reconstituting them into other characters. I never really did do a drawing for Deliscript. All the characters would change a bit as I went through a back and forth process of creating all the letters and characters. I’d start putting different letter combinations and different words together and see where I’d have to align things. I’m still learning and looking at other fonts to understand how to make some of those foreign characters. This process of creating Deliscript took about 6 months and was a constant back-and-forth process.

Deliscript has over 800 glyphs. In this case, it was a guy named Patrick Griffin who was my FontLab life-saver! I couldn’t have it done without his expert help and guidance. He has his own font foundry called Canada Type. Patrick completed all the OpenType programming for Deliscript, and that part of the process took about a month to finish.

It’s only because of OpenType that I could create fonts like Metroscript or Deliscript. It makes accessible to the font designer certain capabilities that weren’t previously available to them. I enjoy creating those little extras because I think it makes it more fun for people, and it gives them the ability to creative with fonts in ways they couldn’t do with fonts before.

Have you seen your other fonts in action?

Metroscript was used in the movie, “The Hulk.†That was pretty cool!

Would you comment on the impact of the computer for better or worse on type design and lettering?

On the one hand, the computer in general has created a lot of lazy people, as far as them being unaware of everything that’s gone on before. If you can’t find it in Google Images, then for most people it might as well never have existed at all. I think that I definitely have an advantage over a lot of other people in that I’ve had the experience of drawing with my hands, of doing actual hand lettering with pen and ink. Curves have a certain tactile or sculptural feel when you can draw them by hand rather than using Illustrator’s Bezier curves. On the other hand I think that I’ve seen a lot of really terrific stuff done with computers that may not have gotten done otherwise. I think it’s a two-edged sword. I know that I was very reluctant to switch over from doing things with pen and ink to the computer. My wife, Laura Smith, who is an illustrator, saw the writing on the wall and she really pushed me to get a Mac. That was back in 1995. And once I did it, I took to it like a fish to water. Most of the work I’d been doing and my whole approach to design had been kind of calculated and mathematical—so translating that to the computer was kind of a no-brainer. Working with Illustrator, I really enjoyed being able to see my work appear instantaneously in color rather than what I used to do, drawing in ink on drafting film. I’d have to work in multiple overlays, one over the other in black ink, and then try to figure out with my best guess on how the color was going to work. And I wouldn’t really know if it would be a success until the finished printed piece came back. I think a lot of the capabilities of what the computer can do are really helpful to people like me because I can experiment graphically with a lot of things that I would otherwise have never been able to do.

Los Angeles has some amazing and battered signs and marquees. Has anything stopped you in your tracks?

I’m thinking every time there’s something good, it gets torn down—like the Brown Derby. But there’s still a lot left. There are huge neon signs on the tops of many buildings here—like The Ravenswood, The Broadway, the Hollywood Roosevelt. There are so many others—The Pantages Theatre, The Frolic Room, the sign over the Santa Monica Pier, Philippe’s French Dip, all the old movie palaces on Broadway…and did I mention Canter’s Delicatessen? There’s still a lot of amazing stuff still out there.

What are 5 things people don’t know about you?

1. When I was around 12 I found myself at a crossroads—it was either a life of art or one of astronomy.

2. One of the most amazing sights I’ve ever seen was the Aurora Borealis on the night that it extended south as far as Brooklyn—and probably beyond. What was almost more amazing was how it seemed that almost no one out in the street bothered looking up.

3. I once did a portrait of Zacherle and sent it to him. I think I remember him displaying it with others on his TV show.

4. Shortly after graduating college I became my roommate’s uncle.

5. My birth name was Dvoretsky—but was later changed by my father.

LINKS

SEE ALSO

Editor’s note: This is the first interview from contributor Alex Savakis. His work can be seen at

www.agsavakis.com

June 8: Mark Simonson and the story of Kandal.

June 15: interview with Jordan Jelev

{ 2 trackbacks }

{ 13 comments… read them below or add one }

Margaret Collins 06.01.09 at 10:52 am

Nicely done Michael Doret. Love your work. Pre computer a whole different discipline, I believe more personal and way more time consuming. I love the ease of the computer but it has no charm. Alex Savakis asked very astute and interesting questions.

Michael Doret 06.01.09 at 2:34 pm

Thank you Margaret. I’d have to say I both agree and disagree with you.

Prior to getting on the computer I worked with drafting equipment on drafting film, creating most of my work as “mechanicals” – pre-sep art. Hardly a medium (such as paint) that has any inherent charm! But the way I see it, the computer is just another kind of paint and brush—as was my old drafting equipment. The qualities that you refer to don’t come from the medium itself, but from the experience and the thinking behind the person using it.

That said, I do believe that there is a lot of work out there that’s way too dependent on digital media, and which does lack the warmth, charm and the personal touch that we all want to see.

Jose Cruz 06.01.09 at 3:35 pm

Michael Doret is the Best Designer I know and no one can top him. His sensibility on Letterform Design is astounding and pure magic. It is a privilege to know his worx and to be his friend.

Joshua Lurie-Terrell 06.01.09 at 4:18 pm

I love Michael’s work, and have been pushing his type since I first saw it. BTW, I am the person who made the neon sign (using Metroscript) that gets destroyed in the Hulk movie. It wasn’t a real neon sign, but a completely digital one. I look forward to using his type in other period typography in movies should I get more jobs like that!

Michael Doret 06.01.09 at 4:33 pm

Hey Josha, my apologies for not mentioning your name on that. I didn’t submit a photo of that sign ’cause I didn’t have a really great still of it (and I haven’t yet seen the film). What you did was still the coolest thing yet that I’ve seen done with Metroscript! And good luck with doing more design work for film.

BTW, didn’t know your website before. Is that a real T-shirt of the plumbing logo?

Luke Dorny 06.03.09 at 11:34 pm

A wonderful interview and writeup. …and great info on creating your fonts, Michael.

Thoroughly enjoyed it.

I especially love fonts created based on the old lettering/signage/logos of the one you found for Gevaert!

Also, very pleased to find out who designed the SNZ art for that album! Great job!

Betsy Snyder 06.04.09 at 8:20 am

Very interesting article. I love hearing what other artists’ influences and experiences are. And great job with the interview, Alex! You seem like a pro at this.

j.millington 06.05.09 at 2:23 pm

SIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIICCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCKKKKKKKKKKKKKKKKKKKKKKKKKKKKKKKKKKKKKKKKKKKKK………………………………………………….

Helen Peck 06.06.09 at 7:19 pm

I knew the Aurora Borealis story but I never knew your complete professional background. It is great to find out the whole story and how you evolved as an artist. I’ve always loved everything I’ve seen you do including, but not limited to, being a really great guy.

Fred Showker 06.08.09 at 6:19 am

EXCELLENT article! Michael is one of the true icons of the typography world — his career has set the bar many times over! Excellent article — we’ll link to it from the Design Center Typography department.

Louis 06.24.09 at 6:50 am

Michael Doret is to typography what Jimi Hendrix was to the electric guitar – he’s in a league all his own. There’s typographers and then there’s Michael Doret. Inspirational Work!

Scott Messer 06.27.09 at 4:06 am

Michael, I’ve loved your work since that classic KISS album cover! I can’t wait to see the latest one as Paul seems pretty excited about it as well. You are one of my early inspirations to become an artist myself. I must have practiced drawing that cover 100 times growing up… Keep on keepin’ on!

Michael W. Archer 07.07.09 at 11:47 am

Mr. Doret;

I am now a huge fan of your work. I have sent this article to many of my designer friends, because I believe your work and influence needs to be seen by everyone that works in the graphic arts. I myself came into this through the back door, but I have been lucky enough to make a modest living at it for the last 15 years. I make yellow pages advertising and phonebook covers. I am more McDonald’s to your Nobu, but I very much enjoy your fonts and letter art and look forward to doing further research into your work. Is there a book about you? There should be.

With Sincerest Admiration,

Michael W. Archer